Intuition vs. Rationality: Insights from Tom W’s Specialty and Bayesian Analysis

In his book Thinking, Fast and Slow, Nobel Prize-winning author Daniel Kahneman discusses the “Tom W’s specialty” problem, highlighting a common pitfall in human decision-making and judgment. This problem is closely related to Bayes’ Theorem in statistics. In this blog post, I will explore how the mathematical concept of Bayes’ Theorem can be applied to decision-making.

Tom W’s specialty

The problem is illustrated through three small tasks. Let’s tackle them one by one. Task 1 Tom W is a graduate student at University X. Please rank the following fields in descending order of likelihood that Tom W is studying in that field:

- Business Administration

- Computer Science

- Engineering

- Humanities and Education

- Social Science and Social Work

In this task, where no additional information about Tom W is provided, it is rational to base the decision on the proportion of students enrolled in each field. The larger the proportion, the higher the likelihood that Tom W is enrolled in that field. These proportions are known as base rates.

Task 2 This task disregards base rates. The following is a personality sketch of Tom W during his high school years: Tom W is highly intelligent but lacks true creativity. He has a need for order and clarity, and prefers neat and tidy systems. He has a strong drive for competence and does not enjoy interacting with people.

Now, please rank the fields again based on how similar Tom W is to the typical graduate student in each field.

Based on this description, it is likely you would rank “Engineering” and “Computer Science” highest, and place “Humanities and Education” and “Social Science and Social Work” at the bottom of the list.

Task 3 So far, so good. The previous two tasks were straightforward. Now, here comes the hardest task. Given the description of Tom W from Task 2, please rank the fields in descending order of likelihood that Tom W is not a student in that field.

If your answer still favors Computer Science and Engineering, you’re in the majority of those who participated in this experiment. And they are so WRONG!

The description of Tom W sounds like a perfect match for students in Computer Science and Engineering. In fact, it was intentionally crafted that way. When performing this task, your System 1—the part of your brain responsible for intuitive thinking—quickly jumps to these conclusions. So why is it wrong? The critical part that most people (possibly including you) overlook is the base rates. If the base rates for Computer Science and Engineering (the number of students enrolled in each major relative to the total number of students) are smaller than those for other fields, such as Humanities and Education, then the likelihood that Tom W is studying Computer Science or Engineering is not necessarily higher. For example, if there are 300 graduate students in Computer Science, 300 in Engineering, but 3500 in Humanities and Education, the likelihood that Tom W is from the Humanities and Education department is still much higher, despite his personality fitting the profile of a Computer Science or Engineering student.

Interestingly, even participants with a background in statistics often fail to make the correct decision. This is a common pitfall in thinking where base rates are completely ignored.

Tom W’s specialty under mathematical perspective

In this section, let’s mathematically formalize the Tom W’s specialty problem using Bayes’ Theorem

\[\begin{equation} P(A∣B)=\frac{P(A).P(B∣A)}{P(B)} % \label{eq:1} \end{equation}\]where:

- \(P(A∣B)\): Posterior, the probability of \(A\) given \(B\)

- \(P(A)\): Prior, the probability of \(A\) without any evidence

- \(P(B∣A)\): Likelihood, the probability of evidence \(B\) given \(A\)

- \(P(B)\): Marginal probability of evidence \(B\) under any condition.

If you are not familiar with statistical terms, don’t worry. You can ignore the jargon because we’re going to apply Bayes’ Theorem in a simple way that everyone can understand.

Let’s say \(A\) is the event that Tom W is a Computer Science graduate student, and \(B\) is the event that he matches the description provided.

In Task 1, where no additional information about Tom W was given, the probability that Tom W is from the Computer Science department is \(P(A)\), which is derived solely from base rates—the proportion of Computer Science graduate students among the total student population at University X.

In Task 2, with the additional description of Tom W, participants were asked to assess the likelihood that a random student matches the description given that the student is from the Computer Science department, denoted as \(P(B∣A)\).

In Task 3, participants needed to determine the probability of \(A\) given \(B\), denoted as \(P(A∣B)\). This should be calculated using Bayes’ Theorem:

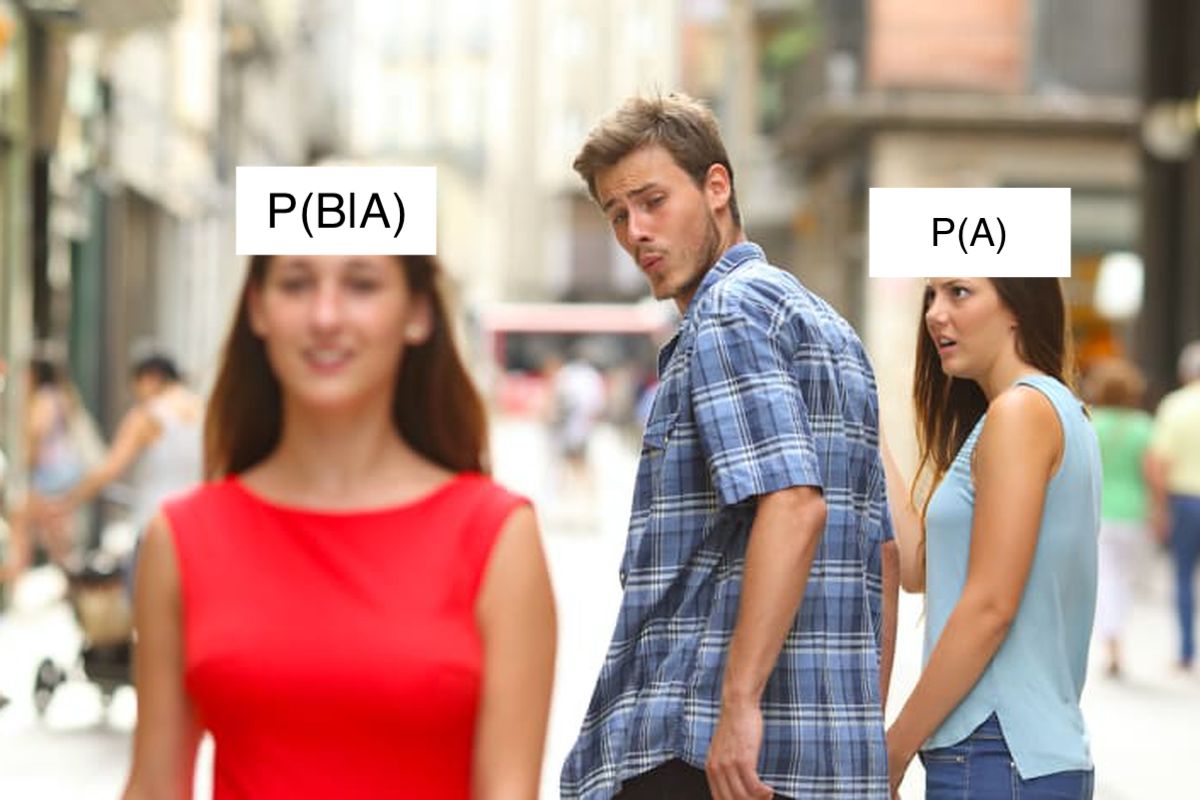

\[\begin{equation} P(A∣B)=\frac{P(A).P(B∣A)}{P(B)} % \label{eq:2} \tag{2} \end{equation}\]The mistake people often make is ignoring the base rates \(P(A)\) and relying solely on \(P(B∣A)\). Their thought process goes something like this: “Oh, the description perfectly matches a Computer Science graduate student, so he’s more likely to be studying Computer Science.”

Let me explain why this intuitive thinking is flawed and why \(P(A∣B)\) is different from \(P(B∣A)\). Even if \(P(B∣A)\) is very high (meaning the description of Tom W fits the stereotypical image of a Computer Science student perfectly), if the proportion of Computer Science students among all students is low (\(P(A)\) is small), the product \(P(A)⋅P(B∣A)\) might not be high. This means that Tom W is not as likely to be a Computer Science student as one might initially think.

Predicting from Representativeness

By now, I hope you understand the common mistake people make in decision-making when they ignore base rates and rely solely on \(P(B∣A)\). The author of the book refers to \(P(B∣A)\) as representativeness. Predicting based on representativeness alone can lead to poor decisions. Here are some everyday examples of predictions based on representativeness, as highlighted in the book:

- In a company, the receptionist appears competent and the furniture is attractive, leading to the assumption that the company is well-managed.

- A start-up looks like it can’t fail, but the base rates of success in this field are extremely low.

The two sins of Representativeness

Predicting outcomes based on intuition and representativeness isn’t a bug in our cognitive system but rather a feature.

Throughout human evolution, we have always sought ways to accomplish tasks with minimal effort to conserve energy for survival. This principle applies to our cognitive activities as well. Intuitive thinking has become our default method because it requires less energy than active, logical thinking. Often, representativeness does reflect the nature of things and phenomena:

- A person who acts friendly is usually friendly.

- A fit person is generally healthier than someone who is not in good shape.

However, there are instances where representativeness can mislead us and drive us to make wrong decisions. Here are the two sins of representativeness that we should be aware of.

1. Representativeness exaggerates rare events

Consider an example from the book. If you see a woman reading the New York Times on a New York subway, which of the following is more likely?

- She has a PhD.

- She doesn’t have a college degree.

Most of us would intuitively say she has a PhD. But let’s apply Bayes’ Theorem to see which is the more rational choice. We define the events as follows:

- \(A\): The woman has a PhD.

- \(B\): She reads the New York Times on the subway.

- \(C\): She doesn’t have a college degree.

The probability that she has a PhD given that she reads the New York Times on the subway, \(P(A∣B)\), is calculated by:

\[\begin{equation} P(A∣B)=\frac{P(A).P(B∣A)}{P(B)} % \label{eq:3} \tag{3} \end{equation}\]Representativeness, \(P(B∣A)\), tells us that a PhD is more likely to read the New York Times than someone without a college degree. However, \(P(B∣A)\) is not what we need to determine. Our brains often choose the representativeness \(P(B∣A)\) instead of the correct probability \(P(A∣B)\) without much verification. Even though \(P(B∣A)\) is high—since a PhD tends to read the New York Times more often than those who didn’t go to college—the base rate of women holding a PhD in the general female population is extremely low (\(P(A)\) is small). This results in \(P(A)⋅P(B∣A)\) being a small number. Meanwhile, the proportion of women without a college degree is much higher (\(P(C)\) is much larger than \(P(A)\)). Despite the lower representativeness \(P(B∣C)\), the product \(P(C)⋅P(B∣C)\) often outweighs \(P(A)⋅P(B∣A)\) due to the disproportionate base rates.

This example demonstrates that our intuition, influenced by representativeness \(P(B∣A)\), can sometimes wrongly exaggerate rare events \(P(A)\), leading us astray.

2. Representativeness Makes Us Ignore the Faithfulness of Evidence

Returning to Bayes’ Theorem, the denominator \(P(B)\) represents how informative or unique the evidence is. It directly influences \(P(A∣B)\) because if the evidence \(P(B)\) is highly informative (small \(P(B)\)), it increases the weight of \(P(A∣B)\), and vice versa.

In Tom W’s specialty problem, \(P(B)\) reflects how reliable the description of Tom W is. Although \(P(B)\) might be uncertain or the portrayal of Tom W might not be accurate, our System 1—the intuitive part of our brain—often assumes it to be true and ignores this factor. The best approach in the Tom W’s specialty problem is to stay close to the base rates \(P(A)\) when we’re unsure about the evidence. We can then make slight adjustments based on our beliefs about \(P(B∣A)\), but ensure these adjustments do not stray too far from the base rate \(P(A)\).

Conclusion

The Tom W’s specialty problem, as presented in Thinking, Fast and Slow, vividly illustrates the pitfalls of relying solely on representativeness in decision-making. By dissecting this problem through the lens of Bayes’ Theorem, we gain a deeper understanding of how our intuitive judgments can lead us astray when we ignore base rates and the reliability of evidence.

In our daily lives, it’s easy to fall into the trap of making decisions based on how well something fits a stereotype or an intuitive pattern. While this can often lead to quick and efficient judgments, it can also result in significant errors, especially when dealing with rare events or uncertain evidence.

By recognizing and correcting for these cognitive biases, we can make more informed and rational decisions. Understanding the importance of base rates and the faithfulness of evidence helps us avoid the two sins of representativeness: exaggerating rare events and ignoring the reliability of our evidence.

Incorporating Bayesian thinking into our decision-making processes allows us to balance our intuitive judgments with a rational assessment of probabilities, leading to better outcomes both in personal and professional contexts. So, next time you find yourself making a judgment based on intuition, remember Tom W, and take a moment to consider the base rates and the true informativeness of your evidence.

Comments